Hungry Horse Project

President Harry Truman threw a switch that ceremonially started power generation at the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation’s Hungry Horse Project in Montana in October1953, and the hard-working facility has been providing electricity to the Northwest ever since. We documented the facility’s impressive history for the Historic American Engineering Record (HAER).

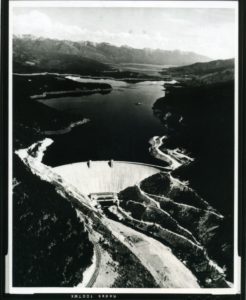

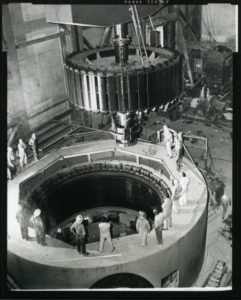

Located on the edge of Glacier Park, the Hungry Horse Project includes a 428 MW power plant, an unusual morning-glory spillway, and a 564-foot-high dam with a 2,115-foot-long crest. It took more than 3 million cubic yards of concrete to create the massive arch dam that filled a deep canyon, impounded the South Fork of the Flathead River, and created a 3.5-million acre-feet reservoir.Reclamation substituted industrial fly ash, a by-product from Chicago smokestacks, for some of the cement in the concrete mix. This material, known as pozzolan, ultimately saved the project more than $2 million and pioneered the use of that material for large dam construction. Reclamation and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers regularly specified fly ash in concrete mixes in subsequent projects.

Located on the edge of Glacier Park, the Hungry Horse Project includes a 428 MW power plant, an unusual morning-glory spillway, and a 564-foot-high dam with a 2,115-foot-long crest. It took more than 3 million cubic yards of concrete to create the massive arch dam that filled a deep canyon, impounded the South Fork of the Flathead River, and created a 3.5-million acre-feet reservoir.Reclamation substituted industrial fly ash, a by-product from Chicago smokestacks, for some of the cement in the concrete mix. This material, known as pozzolan, ultimately saved the project more than $2 million and pioneered the use of that material for large dam construction. Reclamation and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers regularly specified fly ash in concrete mixes in subsequent projects.

Likewise, Hungry Horse was Reclamation’s first major project to use air-entrained concrete. By distributing small air bubbles in the concrete mix, air-entraining agents reduced the effect of freeze-thaw cycles, improved the stability of fresh concrete, and increased the workability of the material—particularly in concrete that had a low proportion of cement because pozzolan was in the mix. The successful results at Hungry Horse led Reclamation to quickly and totally embrace this technology.

and increased the workability of the material—particularly in concrete that had a low proportion of cement because pozzolan was in the mix. The successful results at Hungry Horse led Reclamation to quickly and totally embrace this technology.

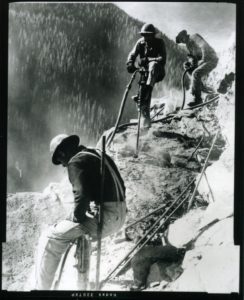

Even before Reclamation awarded large contracts for the project, the sparsely settled region was swarmed by hopeful job-seekers, including many veterans from World War II. Reclamation created a community, “Government Camp,” for its on-site employees, but the private sector jumped in to serve any and all needs of other new arrivals. In 1947, contractors began excavating a tunnel to divert the river while the dam was being built and the prime contract was awarded in April 1948. The ambitious schedule called for placing concrete eight months a year, but Montana’s tough winters reduced that to six or seven months. The dam was high enough by fall 1951 to plug the diversion tunnel and let the reservoir fill.

Today, the Hungry Horse Project continues to generate power, control flooding, and modulate the flow of the river to maximize power production at plants downstream. The utilitarian facility needs periodic upgrades, which are subject to review under Section 106. The HAER documentation provides documentation of existing conditions and serves as a reference for management decision-making.

Today, the Hungry Horse Project continues to generate power, control flooding, and modulate the flow of the river to maximize power production at plants downstream. The utilitarian facility needs periodic upgrades, which are subject to review under Section 106. The HAER documentation provides documentation of existing conditions and serves as a reference for management decision-making.